A Very Brief History of Perspective

The Mirriam-Webster Dictionary defines perspective as “the technique or process of representing on a plane or curved surface the spatial relation of objects as they might appear to the eye; specifically : representation in a drawing or painting of parallel lines as converging in order to give the illusion of depth and distance; or the appearance to the eye of objects in respect to their relative distance and position.

For the artist, seeing, understanding and expressing perspective is an age old problem. Very early artistic drawings and paintings did not show perspective or foreshortening (an aspect of linear perspective which occurs when the size of a form or space is distorted when viewed from a distance or at an unusual angle). Long ago, paintings and drawings made by artists showed the spiritual or thematic importance of figures by size and placement on the picture plane which made space and depth appear distorted.

The Greeks and Romans understood perspective, but over time, their knowledge was lost. Plato wrote, “Thus (through perspective) every sort of confusion is revealed within us; and this is that weakness of the human mind on which the art of conjuring and of deceiving by light and shadow and other ingenious devices imposes, having an effect upon us like magic… And the arts of measuring and numbering and weighing come to the rescue of the human understanding – there is the beauty of them – and the apparent greater or less, or more or heavier, no longer have the mastery over us, but give way before calculation and measure and weight?”

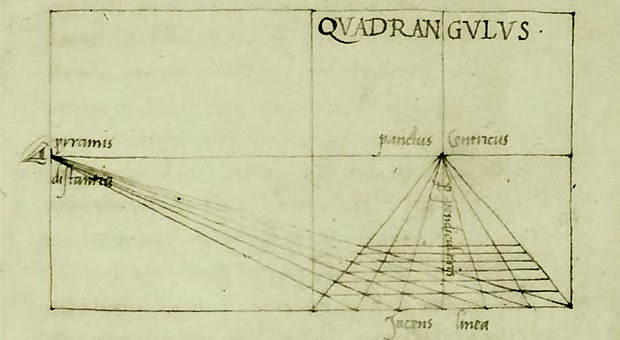

It was 15th Century Italian architect and engineer Filippo Brunelleschi who rediscovered the theory of linear perspective. He demonstrated a mathematical approach that proved how forms and space shrink in size according to their location and distance from the eye.

In 1435 Leon Battista Alberti discovered the first theory of linear perspective and published his treatise Della Pictura (On Painting) in which he too relied on mathematics as the common ground of art and science. Alberti’s discovery had an enormous impact on European artists and is still used by artists, designers and architects today.

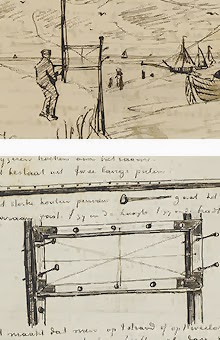

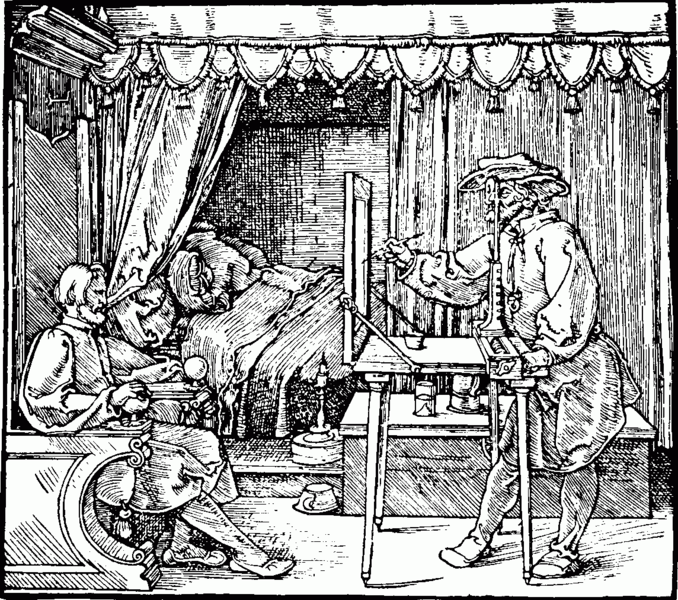

Artists throughout history have devised mechanisms to aid in the recording the reality of the three dimensional world. Leonardo Da Vinci, who was influenced by Alberti and who wanted his paintings to reveal the world as it actually appeared, invented a machine called a Perspectograph. The Perspectograph was comprised of a pane of glass that fit into a frame and which also held a small viewing slot. The framed glass could be placed in front of the scene to be painted. The artist could look through the viewing slot with one eye and then sketch the outline of the scene directly onto the pane of glass. The outline served as a rough sketch for the final, well defined painting.

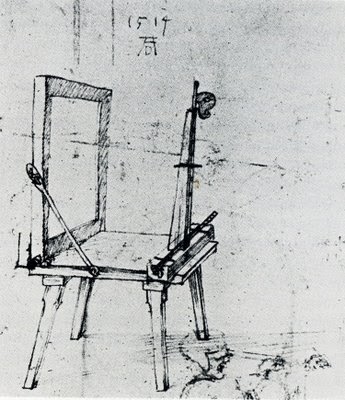

The 1525 German artist, Albrecht Dürer published The Artist’s Manual which included illustrations of perspective machines similar to Leonardo’s Perspectograph, that were designed to enable the artist to make precise measurements of a subject or scene by tracing what was seen through a frame placed directly in front of the artists line of sight.

Translating the reality of the visual world to the flat picture plane is, indeed, a challenging task for the artist and the attempt to discover new and innovative ways to make the process easier and faster will most likely never cease. Conversely, the simple understanding of concepts and theories is an essential aspect of the practice of drawing and painting from direct observation. The use of machines to aid in the discovery of the natural world is a method of enlightening and educating oneself and seems to be a sensible endeavor.